- May 7, 2023

- Jim

- 0

The Department for Science, Innovation and Technology (DSIT – a recent amalgamation of parts of DCMS and BEIS) has just released its seventh Cyber Security Breaches Survey: an annual data gathering exercise across businesses and charities on their approach to cyber security. In the third of our series of blogs reflecting on its findings, we consider the challenges of supply chain security, and offer some suggestions for how companies might take a risk-informed approach to assurance.

After the experience of the last five years, we all know the risks of supply chain reliance. Whether it’s from disruptions to global manufacturing and distribution (COVID), a critical dependence upon suddenly scarce commodities (gas and electricity price rises), or unexpected commercial or financial failures (e.g. Silicon Valley Bank), our businesses are highly vulnerable to the actions of, and impacts on, our third party suppliers.

In cyber, the need to ensure suppliers implement and maintain security is a major challenge. As larger businesses increase their own cyber security, they become harder targets for attackers, who look for alternative ways in. The prevalence of outsourcing and software-as-a-service (SaaS) means that almost all organisations will grant access to their systems to at least some third parties, many of whom won’t necessarily be as strongly guarded as the parent network. Attackers simply go after the ‘weakest link’ to gain access to their ultimate target. Hacking a supplier can also provide access to multiple businesses through one successful attack, rather than exploiting each organisation individually. This means software companies and managed service providers, who may supply hundreds of thousands of customers, are particularly attractive targets, as the recent attacks on SolarWinds (2020) and Microsoft Exchange (2021) demonstrate.

Despite these well-publicised attacks, the 2023 Cyber Security Breaches Survey indicated that only 13% of businesses and 11% of charities review the risks created by their immediate suppliers. The proportion rises to 55% of large businesses. This latter figure represents a rise of 6% since 2022, which is encouraging, but the total numbers are still alarmingly low. This is especially the case when you consider that small and medium enterprises may be more reliant on outsourcing key functions to third-party providers, and thus more vulnerable than larger businesses.

The problem, of course, is that supply chain assurance is really hard: complex, time-intensive, and with 100% assurance impossible to ever achieve. However, there are ways to shore up the weak links in that seemingly never-ending chain. Below we outline three common dilemmas facing those considering how to assure their third party suppliers, and attempt to offer some pragmatic solutions and options to tackle the problems.

How low should I go?

One of the most common challenges facing organisations mapping their suppliers is the complexity and the reach of their supply chains. The 1 in 10 figure quoted by the DSIT survey focused on risks from ‘immediate’ suppliers only, and the number of businesses that manage to successfully map their entire web of dependencies is very low. Once you’ve gone down a couple of tiers, not only does the number of suppliers involved become daunting to assure, but keeping the data up-to-date is almost impossible. With that challenging prospect in mind, “how low should you go”?

In our experience, the organisations who have tackled this issue most successfully are those who have taken a risk-based approach to mapping and managing their supply chains. The first step is understanding which parts of your business are critical to your operations, and which third-party organisations provide or have access to these systems. This should give you a much more targeted view of which suppliers are likely to pose the biggest risk to you, and where you may want to apply requirements to (or at least understand) suppliers below the first tier. Your stationary provider? Unlikely to be a critical dependency. Your deliveries firm, which is both crucial to your just-in-time operating model and which also has access to your customer database? Perhaps worth a closer look.

One of the advantages of digging beyond your immediate suppliers in this targeted way is your increased ability to identify concentration risk. It may turn out that, one tier down, a large number of your suppliers are critically dependent on the same software provider, equipment company, or utility. Or perhaps their supply chains are all geographically concentrated in one region or foreign country. What could start off as a small disruption to one company or geographic area could quickly scale up to be catastrophic for you as the ultimate end-user. It’s worth making sure that, where you do have critical dependencies, that you not only have confidence that your tier one supplier is thinking about their own third party risks, but that you have a high-level understanding of where those points of supplier failure are likely to lie.

Standardise or Individualise?

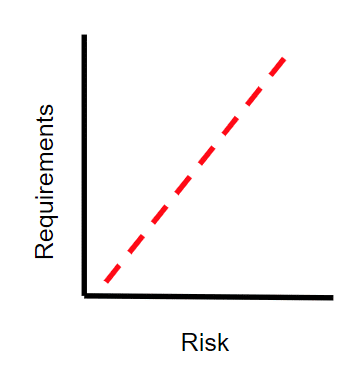

As we’ve discussed, maintaining an up-to-date understanding of your suppliers is complex enough, and that’s before you have started mandating cyber security requirements and assuring their successful implementation. Many organisations try to simplify their assurance in three ways. Firstly, by standardising cyber security requirements across all their suppliers; secondly by ‘outsourcing’ some of the assurance by requiring certification with internationally-recognised and externally audited standards such as Cyber Essentials or ISO 27001. And finally, by skipping ongoing assurance entirely in favour of a contractual liability: namely, you as the supplier commit to being cyber secure, and I reserve the right to sue you if an incident reveals that you aren’t.

The last of these three is obviously risky at best, and not encouraged: no amount of post-facto liability transfer will help your reputation if it’s your services that have been disrupted because of a supplier’s vulnerability. However, the other two approaches do have some advantages. Most significantly, standardisation reduces the resource demand needed both to set and assure requirements, making it more likely that both will be done effectively and regularly by the parent organisation. Meanwhile, specifying accreditation through recognised compliance regimes takes advantage of independent assurance and provides confidence in the suppliers’ ongoing implementation. It can also make it easier and more cost-effective for suppliers to demonstrate compliance and avoids the need for them to develop bespoke information security frameworks for individual clients.

However, there are also a number of possible pitfalls to avoid with these approaches. The first is that standardisation can make setting an appropriate ‘bar’ difficult: how do you design cyber security requirements that can apply equally to your payroll provider and your catering services? Set it too high and you reduce value for money and market interest, too low and you increase your risk. Equally, we often see an over-reliance on external standard compliance that betrays a lack of understanding of what certification means. Cyber Essentials is a fantastic starting point, but it’s a self-assessment (you need Cyber Essentials + if you want external validation). Meanwhile an ‘ISO 27001-certified Information Security Management System’ can represent a wide range of risk tolerances, as the audit considers whether information security policies exist and are effectively implemented, not their stringency.

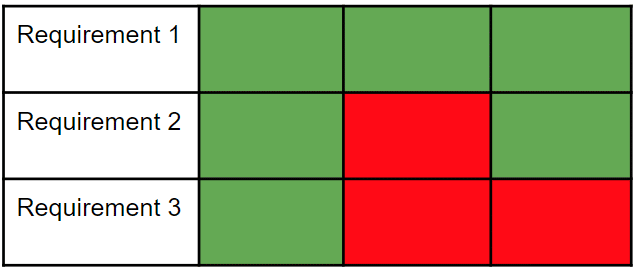

Again, our suggestion would be to take a graduated approach, with different tiers of standardised requirements. A bespoke regime for every supplier may overstretch your assurance capabilities. Instead, group your suppliers by type (e.g. what sort of service they provide) or, even better, by the level of risk they represent to you, and set an increased level of requirements for each tier. This will enable you to maximise efficiencies in your assurance activities, whilst ensuring you maintain an appropriate risk tolerance for the wide range of third parties you work with. You may only want a truly bespoke set of requirements in a couple of cases, for your most critical suppliers or those who have the most access.

Figure 1: two approaches to tiering supplier requirements for cyber security

Diversify or Concentrate?

The final supply chain question that plagues many CISOs is whether to mitigate these risks by diversifying your supply chain, and thereby reducing your reliance on single points of failure, or concentrating your suppliers, and thus reducing the avenues of successful ingress. It’s often a case of ‘damned if you do, damned if you don’t’: diversification increases resilience at the expense of security, concentration increases security at the expense of resilience.

The bad news of course, is that there’s no right answer here, and the decision will depend on a multitude of factors. Here are a couple to bear in mind:

How concentrated is the market? If this is the only supplier that can provide this function for you, diversification may not be an option, so you’ll want to double down on making sure they are secure instead.

How critical is the function they provide? If it’s the service that makes or breaks your operations, consider having a back-up.

How much access to your systems do they require? You’ll want to limit the number of third parties with extensive access by concentrating your providers.

Where does the supplier originate? Is that region or country more prone to potential disruption (natural disasters, political turmoil), or more exposed to security risks (e.g. pressure from parent government to share IP)? If so, you may want to diversify.

One of the worries that keeps CISOs up at night is the fact that, no matter how tight a ship they run, their organisation could be brought down by a vulnerability not of their making. Ultimately, that risk will always exist, and no parent company can monitor every control implemented by every supplier. But as a customer of your supplier’s services, you do have the tools and levers to mitigate your risk, including contractual requirements, mandated penetration tests, ongoing assurance, and external audits. Applying these levers to your suppliers in a risk-informed way will not only ensure you are strengthening the most significant weak links in your supply chain, but will also prevent your team from becoming completely overwhelmed.

Principle Defence can support your organisation with supply chain mapping, requirements setting and ongoing supplier assurance. Contact us to start a conversation about how we might be able to help.